The Fossil Souk

Four hundred million years on the shelf

The trilobite looks like a stone horseshoe crab, curled into a defensive ball. It has compound eyes made of calcite — some of the earliest visual systems on Earth — and a segmented body that flexed when predators approached. It swam in the shallow seas that covered Morocco 400 million years ago, during the Devonian period, when fish were just beginning to crawl onto land.

Now it sits on a dusty shelf in Erfoud, priced at 800 dirhams.

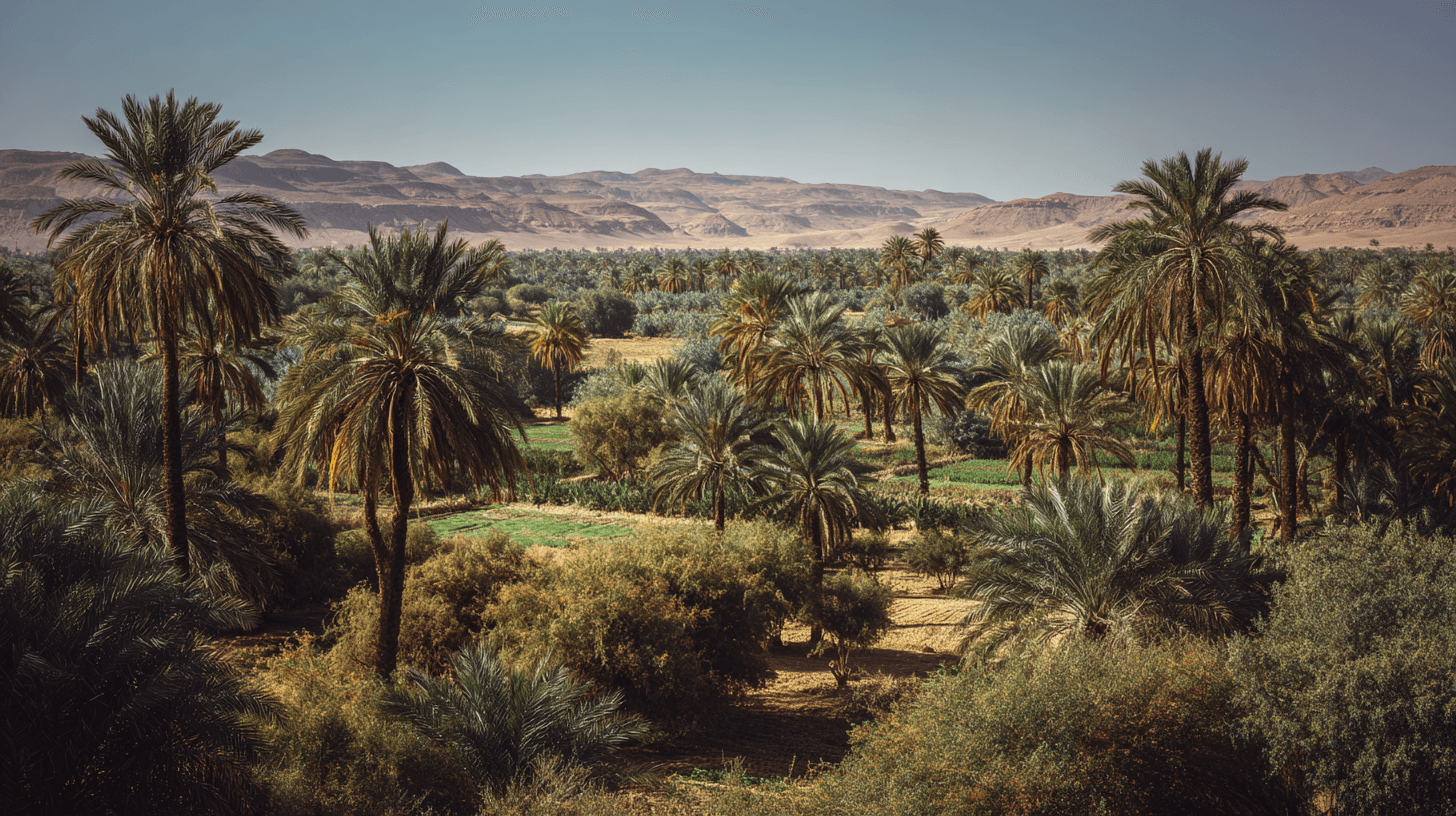

The town at the edge of the Sahara is the fossil capital of Morocco, possibly the world. During the Devonian, this was the floor of a prehistoric ocean. When the water receded, it left behind a geological record so dense that farmers still plow up trilobites in their fields. More than 50,000 Moroccans earn their living in the fossil trade — mining, preparing, exporting. The industry is worth more than $40 million annually.

The fossils include hundreds of trilobite species, many found nowhere else on Earth. Some have elaborate spines and horns. Some are the size of a fingernail; others span a forearm. There are orthoceras — extinct squid relatives preserved in black limestone, their conical shells stacked like organ pipes. There are ammonites, the spiral-shelled ancestors of octopus. There are sea lilies and ancient corals and, occasionally, the teeth of Devonian sharks.

The preparation is an art. Workers extract fossils from limestone using pneumatic tools, then spend hours — sometimes days — with dental picks and brushes, exposing every spine and segment. The best specimens end up in natural history museums from London to New York. The rest fill the fossil shops that line Erfoud's main street, where tourists bargain over coffee tables inlaid with polished orthoceras and bathroom sinks carved from ammonite marble.

Louis Gentil, the French geologist, discovered trilobites near Casablanca in 1916. But the explosion came in the 1980s and 1990s, when fossil collecting became a global hobby. Suddenly there was a market for creatures that had been common in Moroccan rock for eons. The "trilobite economy" was born.

Some worry about what's being lost. The fossil beds around Erfoud have been called the largest open-air fossil museum in the world, but they're being excavated faster than scientists can study them. Forgeries appear — composites of multiple specimens, or creatures enhanced with modern additions. Yet without the market, paleontologists acknowledge, many species would never have been found.

The irony is beautiful. The Sahara Desert — the planet's largest hot desert, a byword for barrenness and emptiness — is one of the richest fossil sites on Earth. Walk through the streets of Erfoud and you are walking through 400 million years of evolution, compressed into stone, arranged on shelves, waiting for someone to take it home.

The Facts

- •Erfoud fossils date to Devonian period — 420 to 360 million years ago

- •50,000+ Moroccans work in the fossil trade

- •Industry worth $40+ million annually

- •Hundreds of trilobite species found, many unique to Morocco

- •Trilobite compound eyes made of calcite — earliest known visual systems

- •Louis Gentil discovered Morocco trilobites near Casablanca in 1916

- •Orthoceras found in black limestone — polished into furniture and decorative items

- •Fossil beds called 'the largest open-air fossil museum in the world'

Sources

- Wikipedia, 'Moroccan fossil trade' — industry overview|Nature.com, 'Green Sahara: African Humid Periods' — geological context|Mint Tea Tours, 'Fossils in Morocco: Famous Sites'|FossilEra, 'Moroccan Trilobites For Sale' — species information