The Invisible River

The khettara as a map of survival

The mounds stretch across the desert in a line so straight it seems impossible without instruments. Each mound marks a vertical shaft. Each shaft connects to a tunnel. The tunnels carry water from the mountains to the oases — underground rivers built by hand a thousand years ago.

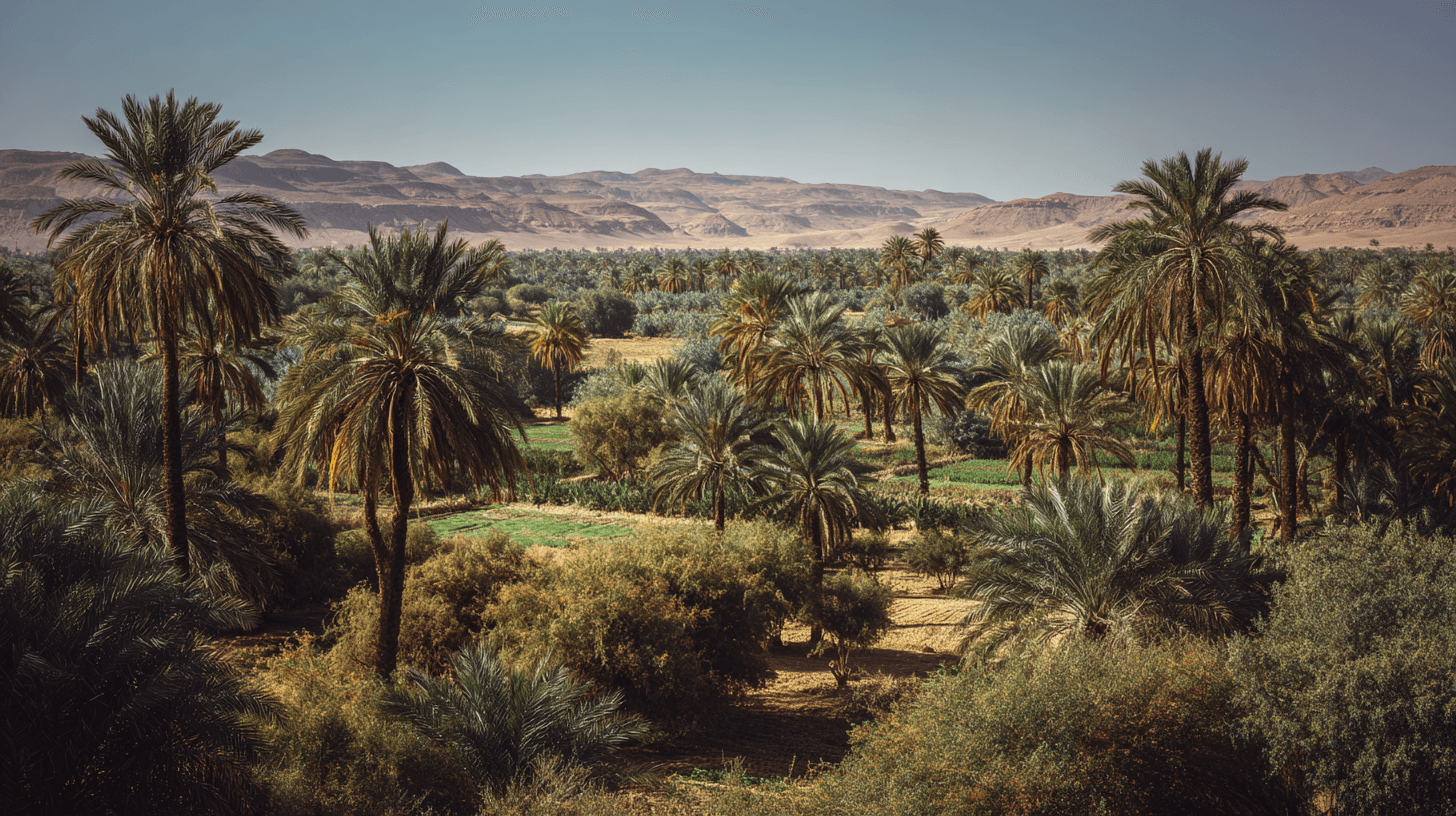

From the air, the khettara system looks like a scar on the landscape. Or perhaps a suture — the stitching that holds life to the desert. The mounds march from the foothills of the Atlas toward the palmeries of Marrakech, Tafilalet, Figuig. They are the visible trace of invisible engineering.

The principle is elegant. At the base of mountains, where snowmelt percolates into aquifers, engineers dug a "mother well" — a shaft deep enough to tap the water table. From this well, they excavated a gently sloping tunnel toward the settlement that needed water. Gravity did the rest. Water flowed downhill through the tunnel, emerging at the surface miles away, filling irrigation channels, fountains, and homes.

No pumps. No energy. Just gradient and gravity.

The construction required brutal labor. Workers descended the vertical shafts — some more than thirty meters deep — and excavated horizontally in both directions, connecting shaft to shaft until the tunnel was complete. They worked by oil lamp in passages barely wide enough to swing a pick. They removed thousands of tons of earth, basket by basket, hauled up through the shafts and deposited in the mounds that still mark the route.

The spacing of the shafts was calculated. Too far apart, and workers couldn't connect their tunnels before running out of air or light. Too close together, and the excavation wasted effort. The standard interval — roughly thirty meters — represents the maximum distance a man could dig before needing ventilation from the next shaft.

This is engineering at human scale. No machines, no external power, just the limits of what a body can accomplish underground.

The khettara of Morocco are part of a tradition that spans the arid world. In Iran, they're called qanat. In Oman, falaj. In Afghanistan, karez. The technology may have originated in Persia three thousand years ago and spread along trade routes to wherever water was scarce and mountains were near. Morocco's systems date primarily to the medieval period, when Arab and Berber engineers adapted Persian knowledge to North African geology.

At their peak, the khettara supported cities. Marrakech — founded in 1070 — grew because underground water could reach it. The gardens, fountains, and palmeries that made the city livable were fed by tunnels dug through the plain. The red walls rose above the desert because invisible rivers ran beneath.

Today, most khettara are dying. Motorized pumps, drilled deeper and running faster, have lowered water tables below the level of the old tunnels. The gravity-fed systems run dry while the electric pumps keep pumping — until the aquifer itself is exhausted. It is a race to the bottom that the khettara cannot win.

But some survive. In the Tafilalet, in the Draa Valley, in scattered oases where communities have protected their traditional rights, the old tunnels still flow. The mounds still march across the desert. The invisible rivers still deliver water from mountain to palm, from snowmelt to fountain, from aquifer to life.

Stand at the outlet of a living khettara. The water emerges cool and clear, flowing from darkness into light. It has traveled miles through the earth to reach this point. It requires nothing — no fuel, no electricity, no maintenance beyond keeping the tunnels clear. It is engineering that runs on physics alone.

This is what sustainability looks like when you strip away the marketing: infrastructure that works with the planet rather than against it, that requires no input except the water cycle itself, that has functioned for a thousand years and could function for a thousand more — if we let it.

Sources

- Lightfoot, Dale. 'Moroccan Khettara.' Geographical Journal

- Ilahiane, Hsain. 'The Social Mobility of the Haratine.' Berghahn

- UNESCO Water Heritage documentation, Tafilalet