The Salt Grids

The currency of taste

From above, the salt pans look like circuit boards — white crystalline grids against red earth, each rectangle a shallow pool where water evaporates and mineral remains. The geometry is ancient and precise: low mud walls dividing the landscape into cells, channels feeding brine from pool to pool, the whole system calibrated to the movement of sun and wind.

This is where white gold comes from.

Before sugar, before oil, before tourism, Morocco was built on salt. The mineral that preserves meat, cures leather, and makes food edible was the foundation of trans-Saharan trade. Caravans carried salt south from the Atlas and Mediterranean coast, exchanging it weight-for-weight with gold from the mines of Mali. A pound of salt for a pound of gold. The equation seems absurd until you understand that gold is merely decorative while salt is survival.

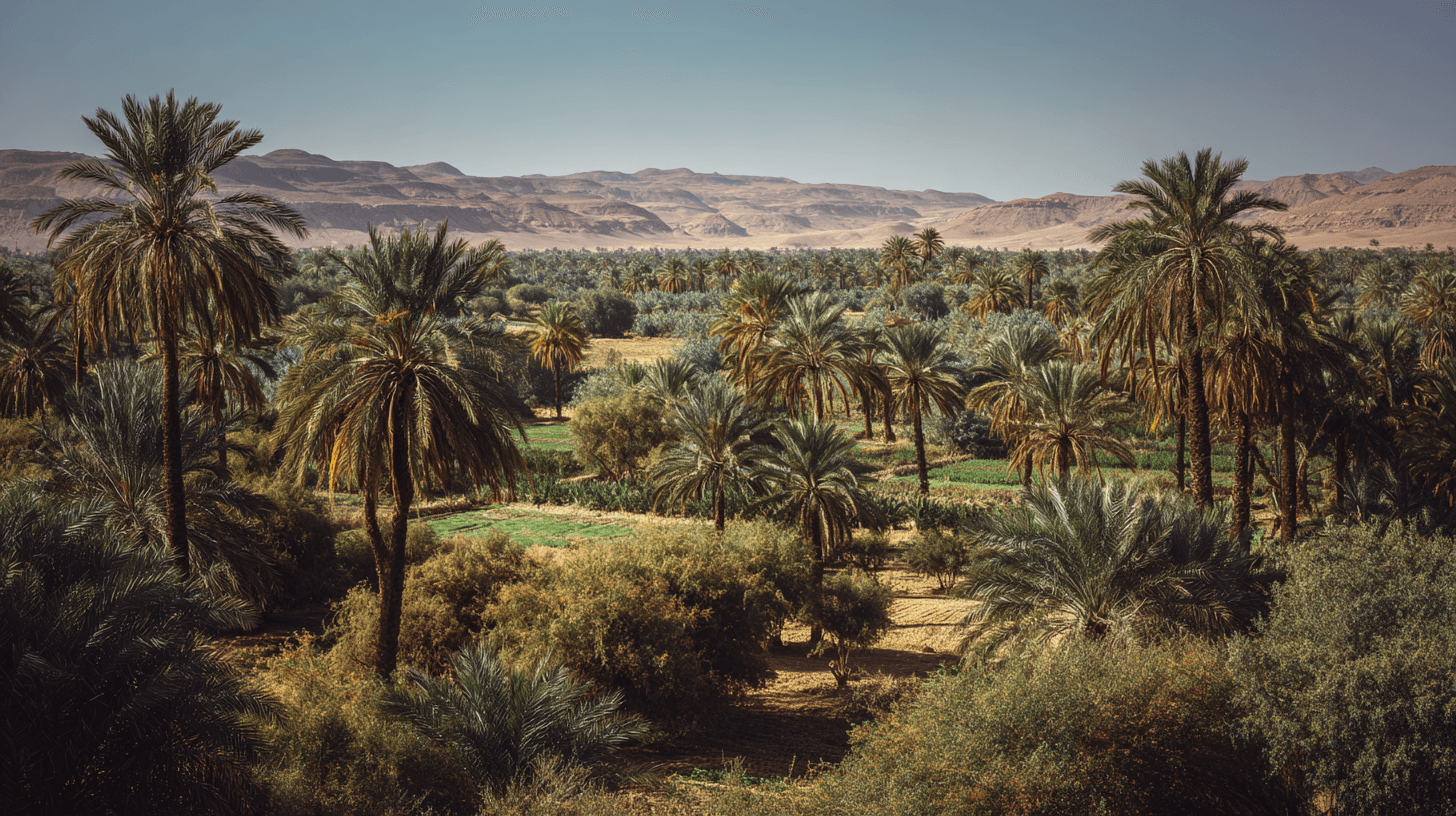

The salt pans of the High Atlas — near Zidania, in the Ourika Valley, scattered across the mountains wherever brine springs emerge — represent centuries of accumulated engineering. The Berber families who work them have inherited not just land but knowledge: which pools to flood first, when to rake the crystallizing salt, how to read the weather for the precise moment of harvest.

The process is patience made visible. Spring water, filtered through salt-bearing rock, emerges from the earth already saturated with mineral. It's channeled into the first series of pools — large, deep, meant for settling. Sediment drops out. The clarified brine moves to shallower pools where evaporation begins. As water leaves, salt concentration increases. The brine moves again, to the shallowest pools, where final evaporation occurs.

What remains is a crust of white crystal against terracotta mud. The workers rake it into piles, then into baskets, then onto the backs of mules for the journey down the mountain. The salt that reaches Marrakech has been refined by nothing but sun, wind, and time.

The architecture of the trade survives in the fondouks — the caravanserais that once housed merchants and their goods throughout the medina. These buildings follow a standard plan: central courtyard, surrounding galleries, rooms for storage and sleeping stacked above. The ground floor held animals and goods; the upper floors held men and negotiations. Salt merchants occupied specific fondouks; leather merchants others; textile traders still others. The city organized itself around commodity.

Most fondouks have been converted now — to restaurants, to craft cooperatives, to boutique hotels. But the proportions remain. The courtyards that once held camels now hold tourists eating tagine. The rooms that stored salt now store luggage. The geometry persists even as the function changes.

In the High Atlas, the salt pans still operate. The families who work them are growing old; their children have left for Marrakech, for Casablanca, for Europe. The knowledge of when to rake, when to channel, when to harvest — knowledge accumulated over centuries — may not survive another generation.

But for now, the white grids still appear against the red earth each spring. The brine still flows. The sun still does its work of transformation, turning water into crystal, crystal into currency, currency into the architecture of a city built on the commerce of taste.

Sources

- Lovejoy, Paul. 'Salt of the Desert Sun.' Cambridge University Press

- McDougall, James. 'A History of Algeria.' Cambridge

- Morocco Salt Federation documentation