The Indigo Trail

The color of the void

The dye doesn't stain — it inhabits. Indigo bonds with fiber at the molecular level, becoming part of the cloth rather than sitting on its surface. Wash it a hundred times and the blue remains, deepening with age, becoming more itself.

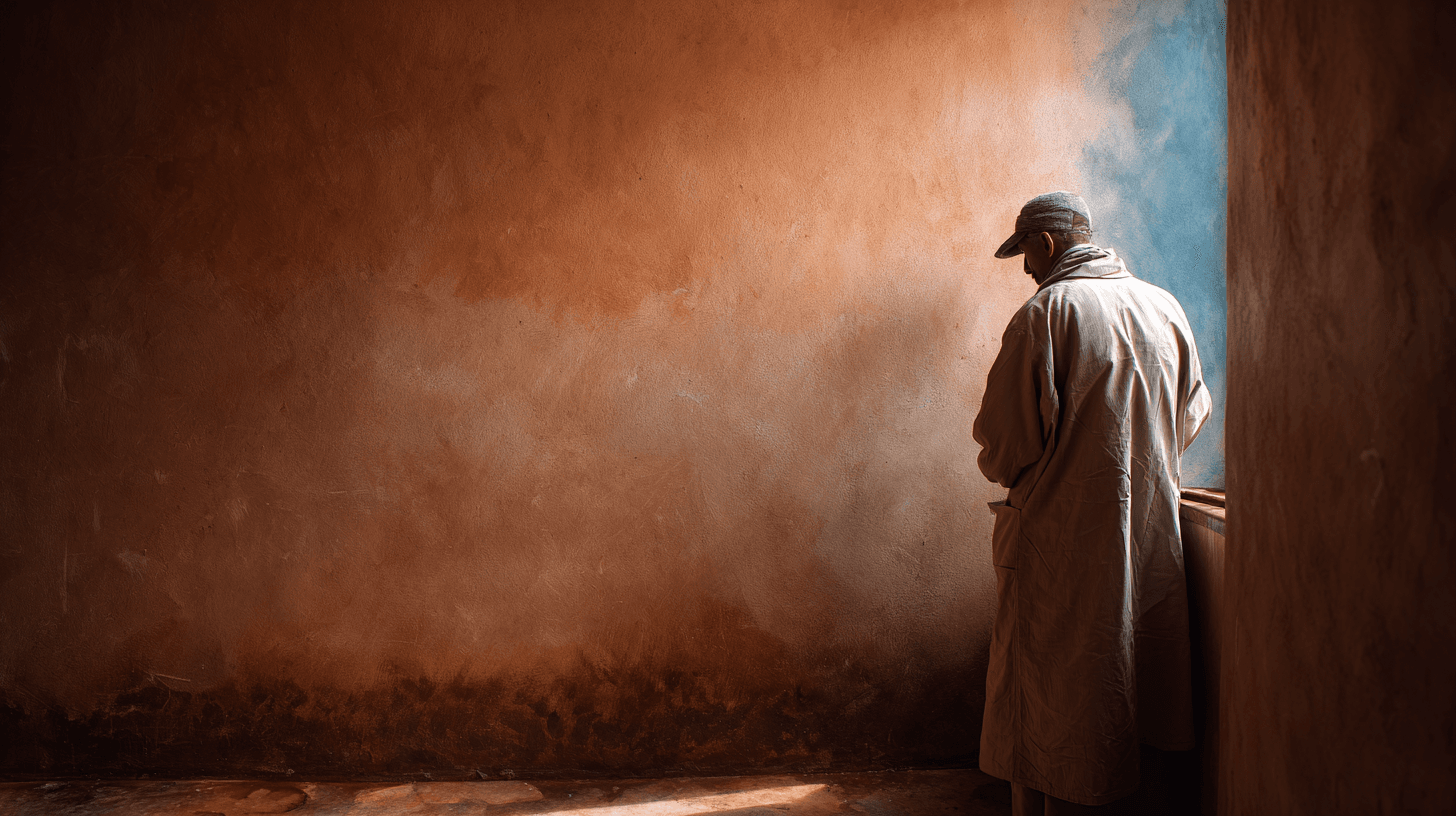

The Tuareg understood this. They called themselves the Blue People — Kel Tamasheq in their own language — not because they wore indigo, but because the color had entered their skin. The heavily dyed cotton of their robes, beaten with wooden mallets to seal the color, transferred indigo to flesh through years of wear. Their faces, hands, and necks took on a permanent blue-gray cast. The dye had become them.

This wasn't accident. It was intention.

In the Sahara, where the sun can blind and the wind carries sand that strips skin, indigo served as protection. The dense cloth blocked ultraviolet rays. The dye itself — derived from the indigofera plant through a fermentation process involving urine, ash, and time — contained antibacterial properties. The color that marked the Tuareg as a people apart also kept them alive.

But indigo carried meaning beyond the practical. Blue was the color of the void — the infinite sky, the endless desert, the space between stars. To wear indigo was to wrap yourself in infinity. The deeper the blue, the more you had traveled, the more desert you had crossed, the closer you had come to the edge of the known world.

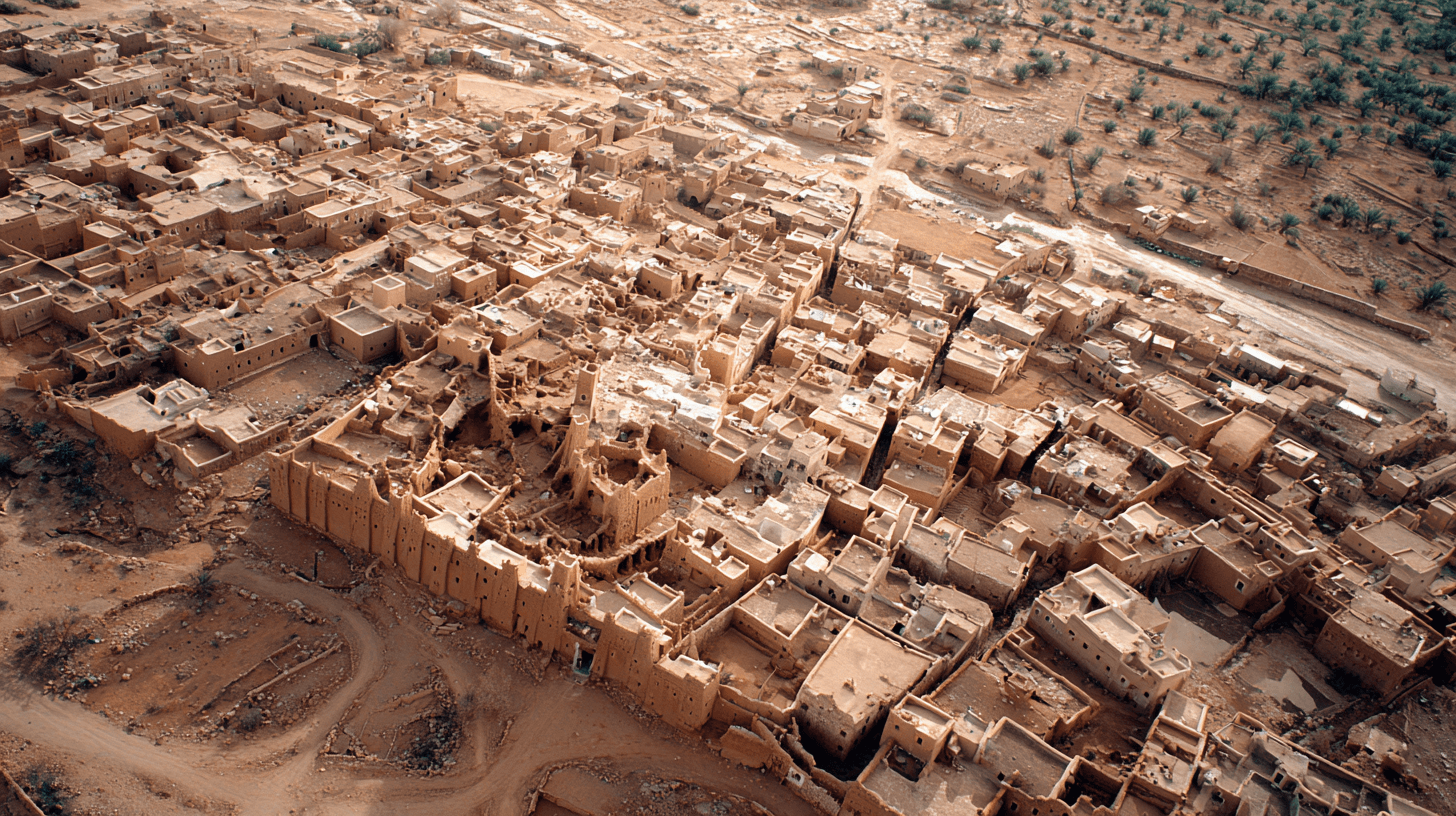

The trail of indigo through Morocco follows the old caravan routes. The plant grew in sub-Saharan Africa — Senegal, Mali, Nigeria — and was traded north across the desert along with gold, salt, and slaves. By the time it reached the souks of Marrakech, indigo was worth more than most spices. The dyers of Fes maintained vats that had been fermenting for generations, each one a living culture of bacteria that transformed plant matter into color.

The chemistry is strange. Indigo is not water-soluble. You cannot simply boil the leaves and dip cloth. Instead, the dye must be "reduced" — chemically altered through fermentation until it becomes soluble, then re-oxidized upon exposure to air. Cloth enters the vat yellow-green. When lifted out, it transforms before your eyes: green to teal to blue to that deep, almost-black that the Tuareg prized above all.

The moment of oxidation is the moment of revelation. You see the color arrive.

In the medina of Marrakech, a few traditional dyers still maintain indigo vats. They work in the tanneries and dye souks, their hands permanently stained, their knowledge passed through apprenticeship rather than books. They will tell you that indigo is alive — that the vat must be fed, must be kept at the right temperature, must be spoken to. They are not being mystical. They are describing microbiology in the language available to them.

The Tuareg trail has faded. The great caravans no longer cross the Sahara; trucks and planes have replaced camels. Synthetic indigo, invented in 1897, killed the plant trade within a generation. The Blue People still exist, but their blue increasingly comes from factory dye rather than fermented leaves.

Yet the meaning persists. In the desert, where everything bleaches to sand and bone, blue remains the color of depth, of water, of sky, of the void that surrounds all living things. To wear it is still to carry protection. To dye with it is still to practice alchemy — transforming plant into color, color into identity, identity into survival.

Sources

- Balfour-Paul, Jenny. 'Indigo.' British Museum Press

- Gerber, Frederick. 'Indigo and the Arab World.' Lulu

- Rasmussen, Susan. 'Those Who Touch: Tuareg Medicine Women.' Northern Illinois University Press