The Khettara

Underground rivers built by hand

Fifty meters below the surface, water moves through darkness. It has been moving for eight hundred years. No one pumps it. No one pays for electricity. Gravity does the work, and the tunnel does not forget its angle.

The khettara is one of humanity's most elegant engineering achievements, and almost no one has heard of it.

Here is the problem it solves: the Atlas Mountains catch rain and snow. That water filters down through rock and collects in aquifers beneath the plains. The water is there, but it's deep — too deep for wells in an age before diesel pumps. How do you bring it to the surface without lifting it?

You don't lift it. You let it flow.

The khettara is a gently sloping tunnel that taps the aquifer at the base of the mountains and carries water downhill to the city or oasis. The gradient is precise — steep enough for the water to flow, shallow enough that it doesn't erode the tunnel. One degree. Maybe two. Calculated by engineers using instruments we've mostly forgotten how to make.

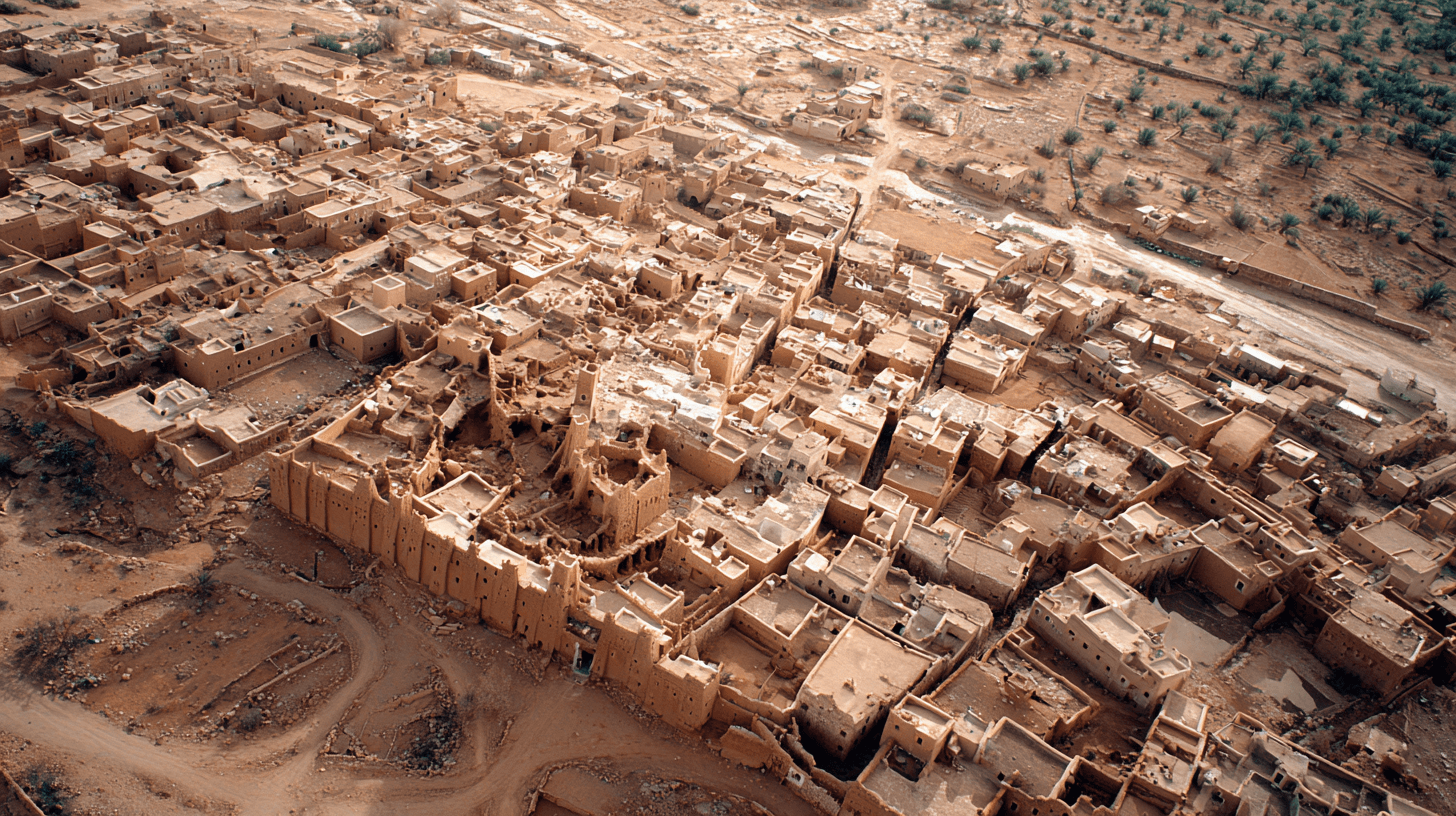

The construction is brutal. Workers dug vertical shafts every twenty or thirty meters, then connected them horizontally, underground, by hand. The shafts served as access points and ventilation. The spoil — the dirt removed to create the tunnel — was piled around each shaft opening, creating the distinctive craters that march across the landscape like a dotted line. From the air, a khettara looks like a string of beads laid across the desert. From below, it's a river in the dark.

Marrakech was built on khettaras. The Almoravids constructed a network that brought water from the Atlas foothills to the growing city. At its peak, more than 500 khettaras fed the palms, the gardens, the fountains that made the Red City possible. The water seemed miraculous — appearing from nowhere, flowing without effort. It wasn't miraculous. It was engineering so good it became invisible.

Now most are dry. Diesel pumps can pull water faster than the aquifer can recharge. The water table drops. The khettaras, designed for a stable water level, find themselves above the water they were built to capture. One by one, they go silent.

Some are being restored. NGOs, local associations, farmers who remember what their grandfathers knew — they're cleaning the tunnels, repairing the collapsed sections, trying to bring the system back. It's not nostalgia. It's survival. The pumps require fuel. The khettara requires only gravity. When the oil runs out, the gradient will still be there, waiting.

Fifty meters below, in the darkness, the water that still flows doesn't know it's ancient technology. It just moves, as it has for centuries, toward the light.

The Facts

- •Khettara (also: qanat, foggara) technology originated in Persia ~3000 years ago

- •Brought to Morocco by Arab/Persian engineers in medieval period

- •Marrakech once had 500+ khettaras feeding the city

- •Tunnels can extend 10-20km from mountain aquifer to city

- •Vertical shafts every 20-30m for access and ventilation

- •Gradient typically 1-2 degrees for optimal flow

- •Most Moroccan khettaras now dry due to falling water tables

- •Some restoration projects underway with NGO support