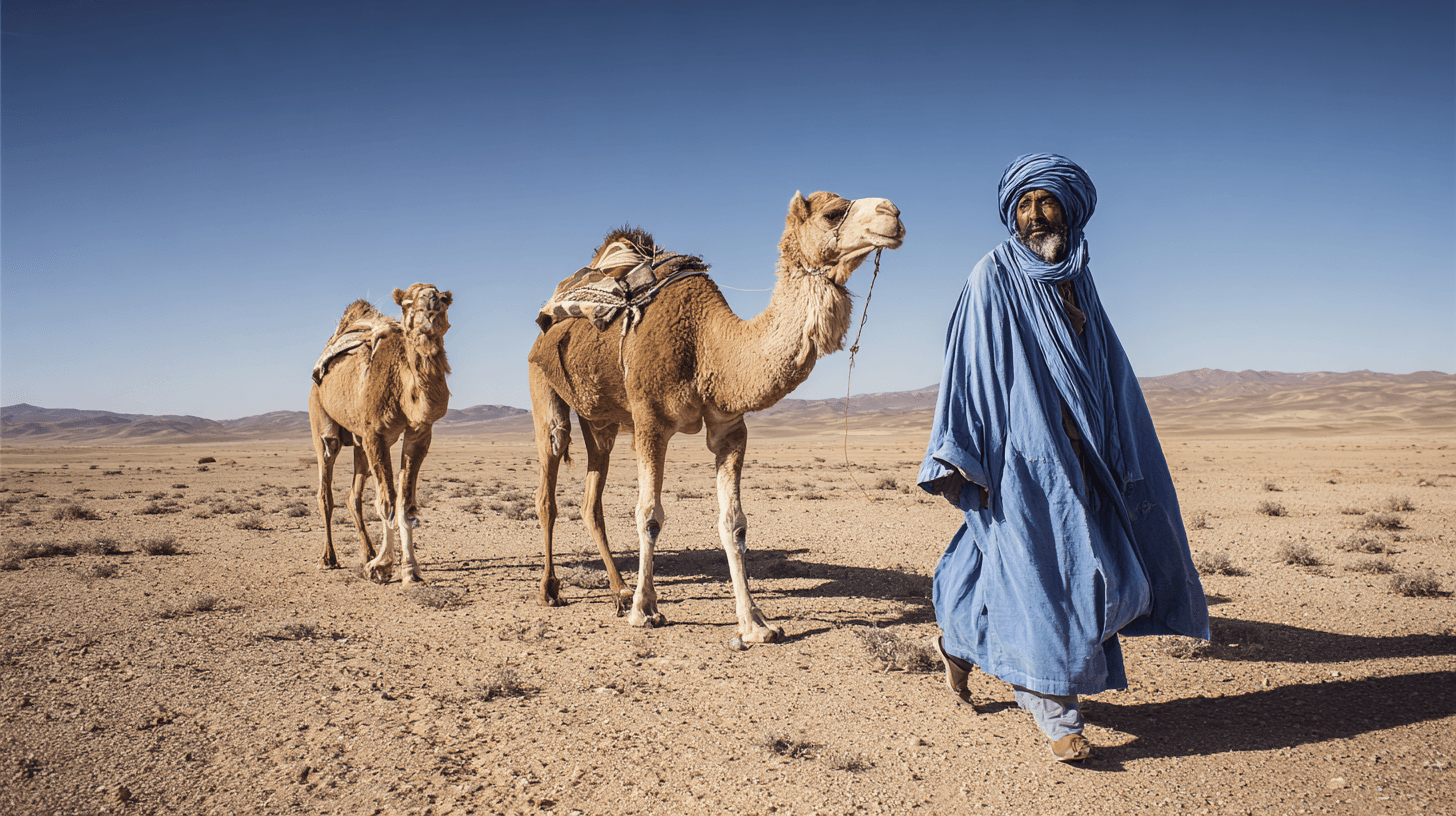

The Last Nomads

They navigate by stars, read water in rock color, and move 40,000 sheep twice a year. The Sahara's memory keepers.

Everything has changed,' said Moha Ouchaali, his wrinkled features framed by a black turban. 'I do not recognise myself anymore in the world of today. Even nature is turning against us.'

Near the village of Amellagou, 280 kilometers east of Marrakesh, Ouchaali and his family have pitched two black woolen tents beside a dry riverbed. One for sleeping and guests, one for cooking. The view has not changed in centuries. The water has.

Morocco's 2014 census counted 25,000 nomads—down by two-thirds in a single decade. A 2025 Carnegie study estimates the current population at closer to 12,000. The anthropologist Ahmed Skounti, himself from a nomadic family, predicts the lifestyle will disappear entirely within ten years. 'If these people, used to living in extreme conditions, cannot resist the intensity of global warming,' he says, 'that means things are bad.'

The Ait Aissa Izem once moved three times a year—summers in the cool mountain valleys of Imilchil, winters in the lowlands around Errachidia. Now they move once, if at all. The traditional routes are 'ancient history,' says Moha Haddachi, head of their community association. Pastures have been privatized. Agricultural investors dominate grazing lands.

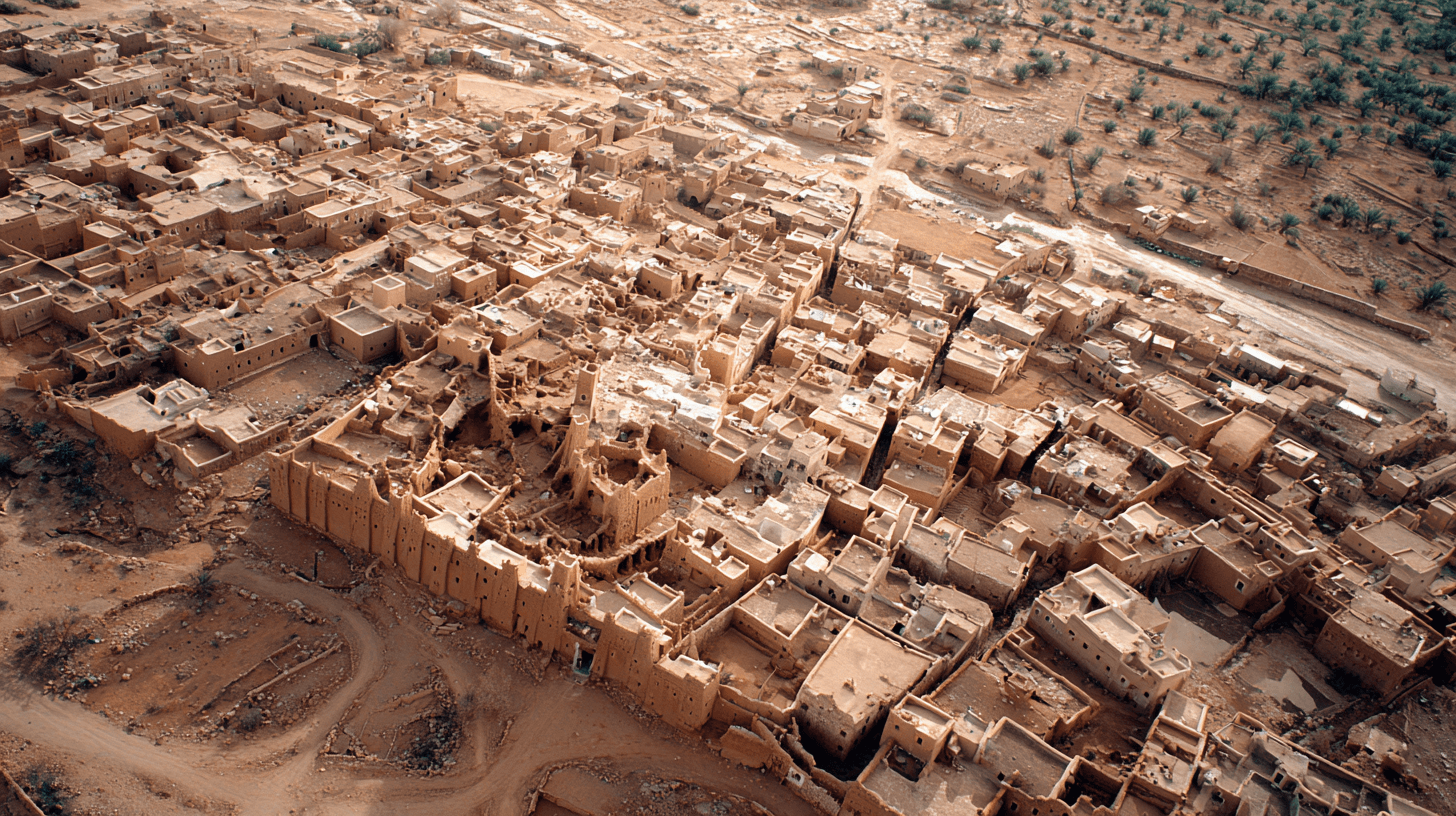

Near the dunes of Merzouga, the Ait Khabbash have built something unexpected: a tourism industry from the ground up. Desert camps offering treks, meals, and nights under the stars. The transformation began modestly in the 1970s and expanded by the early 2000s, now providing thousands of jobs.

But tourism is fragile. When COVID-19 collapsed global travel, many who had transitioned to the industry lost everything overnight. Some returned temporarily to their herds. Others had already sold them.

'I was tired of fighting,' said Haddou Oudach, 67, who settled permanently in Er-Rich in 2010. 'We have become outcasts from society.'

The government installs solar-powered water pumps on wells, subsidizes animal feed, provides direct aid. It is not enough. Near the town of Assoul, the nomadic community once numbered 650 family tents. Now: 83. The rest have moved to cities—Ouarzazate, Marrakesh, some to France and Spain. Many men work in tourism when there are tourists, construction when there are not.

Morocco experienced its worst drought in four decades in 2022. Rainfall is projected to decline another 11 percent by 2050. The nomads who remain take loans to buy fodder so their animals do not starve.

The Facts

- •Red ironstone indicates water within 200 meters due to iron oxidation

- •Saharan navigation routes have been used for over 3,000 years

- •Routes are encoded in songs and oral poetry passed down generations

- •GPS and satellite navigation fail during sandstorms

- •The number of practicing nomads decreases each year

- •Traditional navigation requires knowledge of geology, astronomy, and memorized routes

- •Some families still practice full nomadic life in the Draa and Tafilalet regions

Sources

- France 24, 'Moroccan nomads' way of life threatened by climate change,' October 3, 2022 Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, 'Beyond the Green Transition: Governance and Climate Vulnerability in Morocco,' March 2025 Carnegie Middle East Center, 'Between Marginalization and Climate Change: The Resilience of Morocco's Ait Khabbash,' November 2025 Morocco World News, 'Climate Change Disrupts Moroccan Nomads' Lifestyle,' October 2022 PBS, 'Meet the Amazigh Nomads Fighting Climate Change in Morocco,' September 2023 Interview with Ahmed Skounti, anthropologist, INSAP Rabat