The Medina Logic

The labyrinth that isn't random

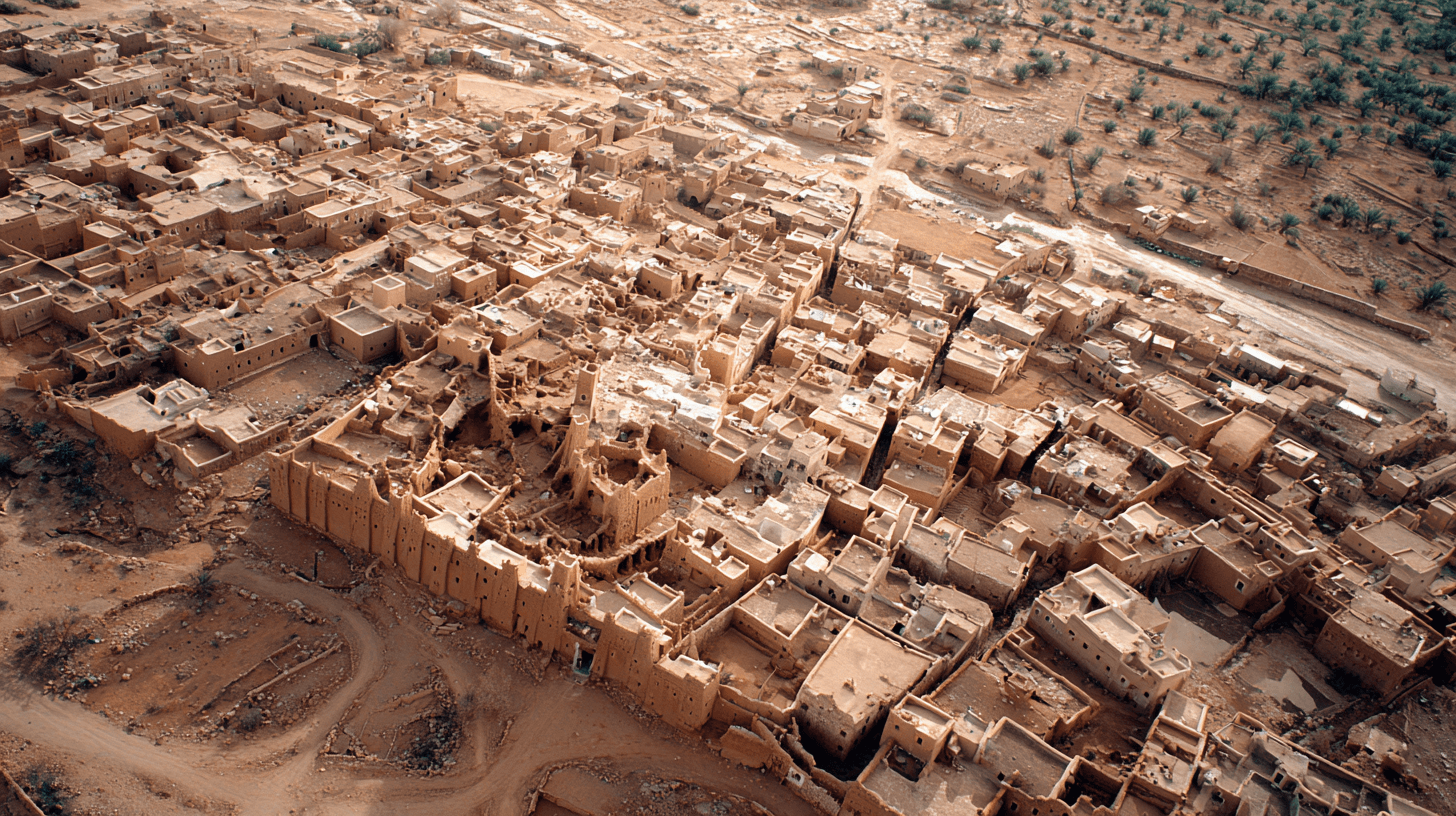

Every tourist gets lost in the medina. They think it's chaos.

It isn't.

The medina is a machine — organized by trade guild, by tribe, by origin. Each street has a function. Each turn has a reason. The labyrinth follows rules that were old when the first European wandered in and got lost.

Start with trade. The tanneries sit near the river because they need water to wash hides and wind to carry the smell away from everyone else. The dyers cluster nearby — same water, same logic. The goldsmiths and silversmiths set up near the main mosque, where trust matters and customers are pious. The blacksmiths work at the edges, where their noise and fire won't disturb the scholars. The food sellers position themselves at the gates, catching travelers on arrival.

The pattern repeats in every Moroccan medina. Fes, Marrakech, Meknes, Tétouan — the same guilds, the same spatial logic, the same answers to the same problems. A thousand years of trial and error, encoded in stone.

Now follow the width of the streets.

Main arteries are wide enough for a loaded donkey. These are public — anyone can walk them, and they lead to mosques, markets, foundouks. As streets narrow, you're moving toward the private. A derb that tightens to shoulder-width is telling you something: residents only. A dead end isn't a mistake — it's a security feature, forcing strangers to turn back, protecting the families who live beyond.

The medina was designed before addresses existed. Locals navigate differently. Not by street names — most streets don't have them — but by landmark, by smell, by sound. Turn left at the fountain with the broken tile. Straight until you smell the spice souk. Right when you hear the coppersmiths. The medina is read with the body, not with maps.

GPS fails here. The satellites can see you, but they can't see the architecture. Alleys twist under buildings, through tunnels, up stairs that don't register as streets. The apps show you ten meters from your destination while you face a blank wall. The medina was built to defeat exactly this kind of surveillance.

That was the point.

A medina has no straight sightlines. No vantage points where an outsider can stand and understand the whole. The streets curve deliberately, blocking views, creating pockets of privacy in the densest urban fabric on earth. An invading army couldn't charge through — they'd be funneled into chokepoints, picked off from above, lost in a maze designed to swallow them.

The same architecture that protected residents from medieval invaders now protects them from tourists. The confusion isn't a bug. It's a feature so old that everyone has forgotten it's a feature.

Learn to read the medina and the chaos resolves. The wider street leads to commerce. The narrower street leads to homes. The dead end protects a family. The covered passage connects two neighborhoods that needed connecting. The fountain marks a crossroads. The tree marks a saint's tomb. The bent door — never a straight entrance — prevents the evil eye from looking in.

Every tourist gets lost in the medina. The ones who understand why are no longer tourists.

They're reading a manuscript written in streets.

The Facts

- •No straight sightlines — deliberate security feature

- •Streets organized by guild: tanners near water, goldsmiths near mosque

- •Width indicates privacy: narrower = more residential

- •Dead ends are security, not mistakes

- •Predates street addresses by 1,000+ years

Sources

- Bianca, Stefano. Urban Form in the Arab World. Thames & Hudson

- Le Tourneau, Roger. Fes in the Age of the Marinides. University of Oklahoma Press

- Minca, Claudio. 'The Medina: A Western Myth.' European Urban and Regional Studies