The Water Masters

Men who listen for underground rivers

He walks the dry riverbed in bare feet, stopping every few meters to press his palm against the sand. The rest of us see nothing. He sees a well worth digging.

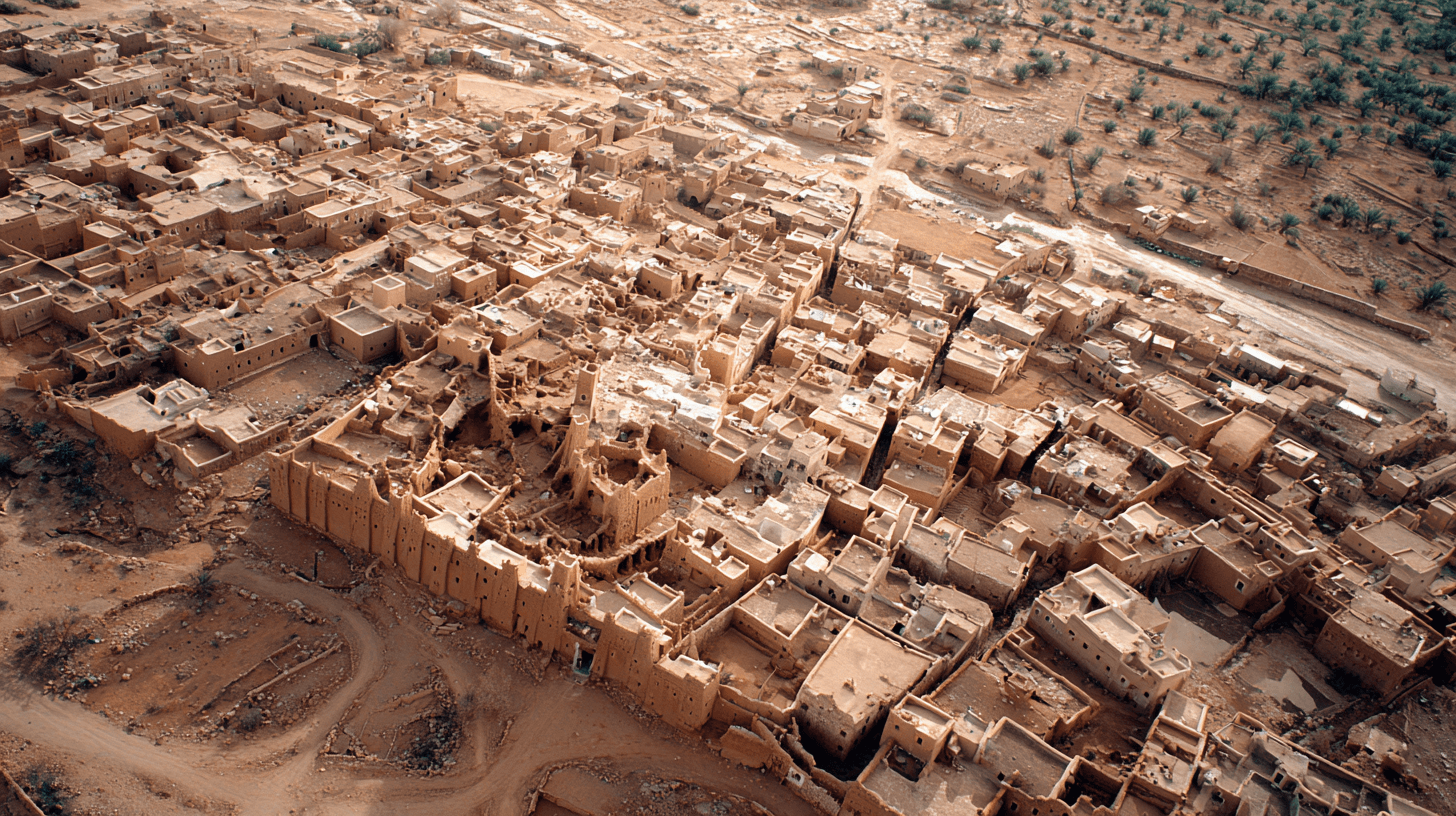

In the pre-Sahara, where rain falls perhaps twice a year and every drop matters, there are still men who can find water by reading the land. They are called maalem el-ma — masters of water — and their knowledge passes from father to son along lines stretching back beyond memory.

The skill looks like magic. A water master walks terrain that appears uniformly dry, uniformly hopeless. He studies vegetation too subtle for outsiders to notice — a slightly greener cast to the thorns, a particular species of salt-tolerant shrub. He looks at the lay of the land, the color of the rocks, the way wadis branch and join. He listens to something the rest of us cannot hear.

Then he marks a spot. "Dig here."

The science, to the extent it can be called that, involves reading the landscape as a hydrological system. Water follows paths determined by geology. It pools in specific structures, at specific depths, in specific relationships to surface features. What looks like intuition is actually pattern recognition honed over generations — a mental model of underground flow built from thousands of successful and failed wells.

The maalem learns by apprenticeship. As a child, he walks with his father, watches where he looks, hears his explanations. "See how the tamarisk leans? Follow the lean." "Feel the temperature of the sand — cooler here means water beneath." Over decades, the lessons accumulate into something that looks effortless.

Diesel pumps have changed everything and nothing. The pumps are faster, but they need to be told where to pump. Satellite surveys help, but they cost money and miss subtle aquifers. When a village needs water, they still often call for a maalem el-ma — an old man who walks the land in bare feet, feeling for the pulse of the earth.

He marks a spot. They dig. The water comes. He accepts tea, refuses payment, and walks back to his village. The skill is not for sale. It is held in trust, for a landscape that needs every drop it can keep.

The Facts

- •Maalem el-ma tradition documented for 1,000+ years

- •Skills passed through apprenticeship over decades

- •Methods combine geology, botany, and hydrology

- •Success rates reported at 80%+ in experienced practitioners

- •Modern dowsing differs from traditional landscape reading

- •Some families maintain water-finding lineages for 10+ generations

- •Diesel pumps reduced but didn't eliminate demand for traditional methods

Sources

- Geertz, Clifford. 'Islam Observed.' University of Chicago Press

- Bencherifa, Abdellatif. 'Water Harvesting Systems in Morocco.' FAO

- Ilahiane, Hsain. 'Traditional Water Management Systems.' Journal of North African Studies