The Wedding Market

Every September, 30,000 people gather in the High Atlas for a mass matchmaking that traces back to two drowned lovers

The lakes are called Isli and Tislit — "the groom" and "the bride."

According to Berber legend, a young man from the Aït Ibrahim tribe fell in love with a girl from the Aït Azza, enemy clans whose feuds stretched back generations. Their families forbade the marriage. The couple wept so much they cried themselves to death, their tears forming the two lakes that still sit in the High Atlas, separated by a mountain ridge.

Even in death, they couldn't reach each other.

The tragedy shamed both tribes. They vowed that no young lovers would ever be separated again. And so they created the Moussem of Imilchil — an annual festival where young men and women from any tribe could meet, court, and marry whoever they chose. No family could object. No feud could interfere.

That was centuries ago. The festival still happens every September.

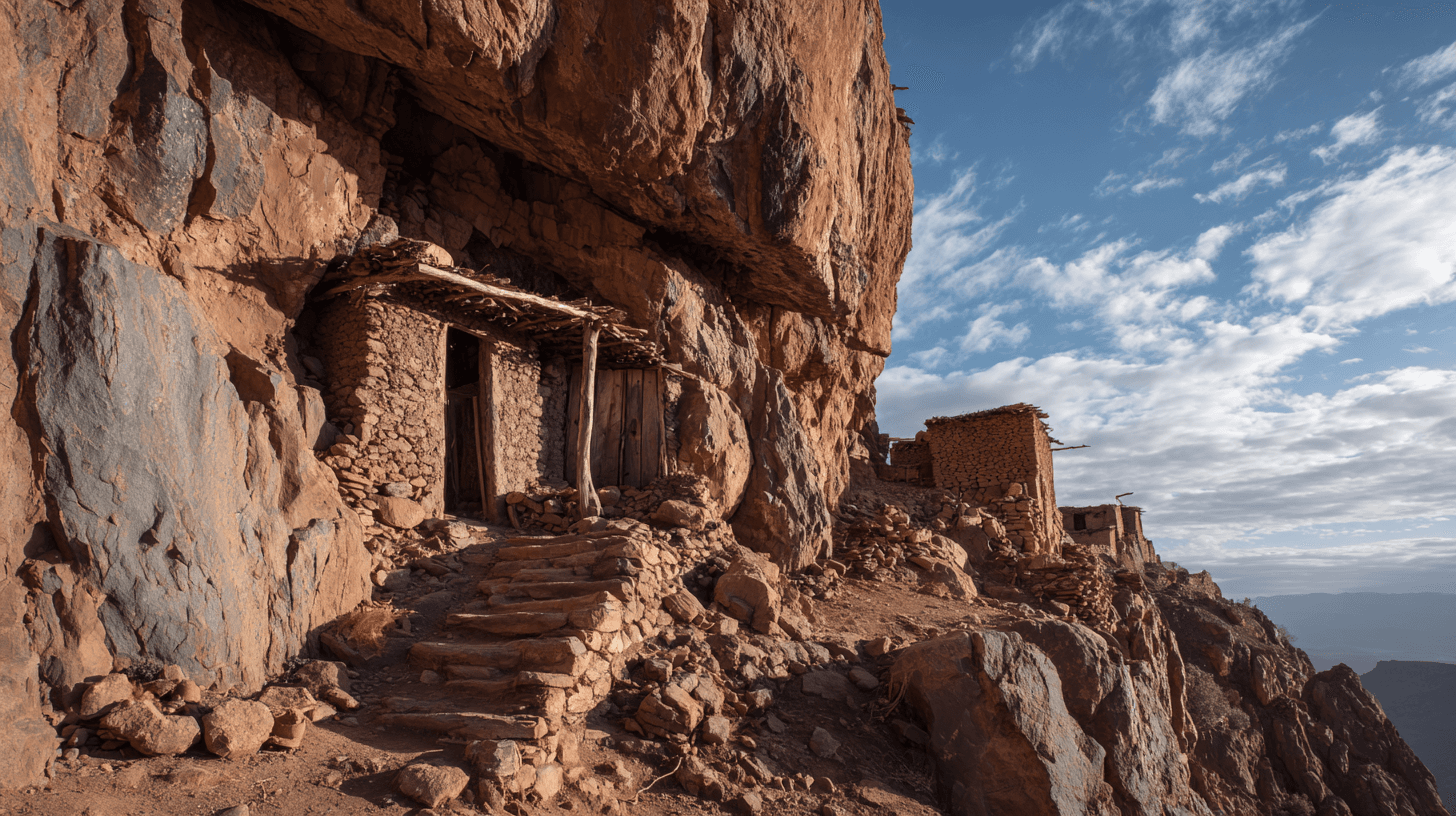

Up to 30,000 people descend on the small village of Imilchil, population 2,000. They bring tents, livestock, goods to trade. For three days, the mountain plateau becomes a temporary city. Young men wear white djellabas; young women dress in traditional handira blankets heavy with silver jewelry, their eyes lined with kohl.

The courtship is formal but fast. If a woman likes a man, she tells him: "You have captured my liver." Not the heart — the Berbers believe love lives in the liver, the organ of wellbeing. If he agrees, they meet with their families in a tent. Questions are asked over mint tea. If everyone consents, a marriage contract is drawn up on the spot.

The actual weddings happen later, in home villages. But the engagement is binding. Dozens of couples are matched in those three days.

Divorced and widowed women come too — they wear a distinctive pointed headdress so suitors know they're available. In Berber culture, remarriage carries no stigma. The festival is practical as much as romantic: in isolated mountain villages where young people rarely meet outsiders, Imilchil is the chance to expand the gene pool and strengthen alliances.

Tourists have discovered the festival in recent years. There are concerns about authenticity, about spectacle. But the marriages are real. The contracts are legal. And every September, the descendants of two drowned lovers prove that tragedy doesn't have to be permanent.

The lakes still sit there, separated by the ridge. The lovers never did reach each other. But their children did.

The Facts

- •The festival takes place in mid-September annually (2025 dates: September 18-21)

- •Up to 30,000 people attend from surrounding tribes

- •The village of Imilchil has only about 2,000 permanent residents

- •Lakes Isli ('groom') and Tislit ('bride') are real — separated by a mountain ridge

- •Women say 'you have captured my liver' — not heart — to express love

- •Divorced and widowed women wear a pointed headdress to indicate availability

- •The festival has been held for centuries, though exact origins are debated

Sources

- Becker, Cynthia. 'Amazigh Arts in Morocco.' University of Texas Press

- Morocco World News documentation

- Insight Guides Morocco